This Op-Ed was originally published by The Washington Post

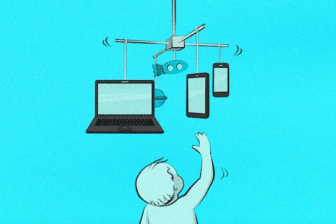

Babies need people, not devices. Stop giving them screen time.

By: Susan Linn

August 29, 2023

We know a great deal about what babies and toddlers need to thrive: food, shelter, safety, love and medical care. In addition to those basics, they also require, and actively seek, repeated, positive, real-life interaction with their caregivers — fulfilling an inborn need for relationships that our increasingly online world threatens to disrupt. Smartphones, tablets and other digital distractions draw the attention of babies and caregivers away from one another to whatever beckons from a screen.

It’s hopeful news that government officials are calling for regulations on tech companies’ marketing to children and adolescents. But the public discourse often leaves out products aimed at babies and toddlers, despite a growing body of research demonstrating that, for children younger than 2, hours of screen time can harm their physical, social, emotional and cognitive development.

It’s not that infants are posting on Instagram. But they are not exempt from the lure of new technologies, including social media. Tech aimed at babies abounds on TikTok and YouTube. Videos attracting millions of views market themselves as a godsend to stressed parents. Some promise to make babies stop crying;others claim to soothe colicky infants. Yet evidence suggests that routinely using devices to soothe young children deprives them of opportunities to rely on caregivers for comfort — opportunities crucial to developing their own resources to soothe themselves.

Other offerings make patently false claims that they teach babies to talk or “boost” babies’ learning while parents “get some time back.” Yet we now know that babies can’t learn language from machines. They learn to speak in relationship to humans who love and nurture them. In fact, for infants and toddlers, more time with screens of all kinds is associated with delayed language development.

As for “boosting” infant learning, the opposite seems to be true. New studies of infant and toddler brain development and behavior suggest that frequent screen exposure is linked to diminished capacity for two traits crucial for success in school and for coping with all sorts of life challenges: executive function and self-regulation. The former refers to the capacity to initiate tasks and see them to completion; the latter has to do with self-control, including the capacity to delay gratification and to manage powerful emotions without harming oneself or others. Equally concerning, more screen time before 12 months is linked to delays in communication and problem-solving at ages 2 and 4.

The World Health Organization and pediatric associations worldwide recommend avoiding screen time for babies and toddlers. Yet in the United States, almost half of children under age 2 have daily screen time, and about one-third spend more than an hour each day with devices. Eleven percent spend more than two hours per day with screens, and of these, 7 percent spend more than four hours. Moreover, studies have shown that the more time children spend with screens as babies, the more time they’re likely to spend with devices when they’re older.

It’s tempting to conclude from the above figures that public health recommendations don’t work, or to blame parents for ignoring them. But a recent study of adherence to screen time recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics offers another, more hopeful explanation. Less than two-thirds of the parents surveyed knew of the guidelines; less than half could cite them accurately; and most parents who allowed their youngest children screen time were under the impression that it had educational benefits.

Clearly, accurate information about babies and screens is not getting through. But there are several ways to combat this.

First, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Health and Human Services should invest in a public health campaign to alert parents of infants and toddlers to the lack of educational benefits from tech and media and to the potential harm of their repeated use.

Second, government should hold companies promoting media for babies accountable for false and deceptive marketing — just as legislators are seeking to prevent social media companies from marketing unfairly to teens. Regulatory agencies can require that educational claims about apps and games for young children be supported by independent research. Fines for app and media companies’ noncompliance should be substantial enough to prevent false advertising about their products’ educational benefits.

Finally, the people most likely to interact directly with babies and their parents should be enlisted to help. Child-care providers, educators, community organizers and health professionals can support parents in efforts to avoid screens and offer them real-world strategies for stimulating and soothing infants and toddlers. Pediatricians are obvious messengers, but helping parents resist industry efforts to hook babies on screens needs to begin before birth, with obstetricians and midwives.

Babies need people, not devices. They need to be cuddled, talked to, played with and read to by the adults who love them. For evidence of this, you need look no further than the face of any weeks-old baby staring up at you, looking to make eye contact — to connect

Susan Linn, a psychologist, is a research associate at Boston Children’s Hospital, a lecturer on psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and the author, most recently, of “Who’s Raising the Kids?: Big Tech, Big Business, and the Lives of Children.”